When I see grass-fed beef in local markets, I imagine cattle grazing in a pasture. Those animals were living the good life, I figure, so I feel better about eating them.

As with many things, I discovered, the reality often is very different.

All cattle graze at some point. “Even in conventional feedlots, the diet is usually 15% roughage of some sort (ground hay, silage, straw, etc.),” says Jim Gerrish. As owner of American GrazingLands Services in May, Idaho, he advises producers on environmentally sustainable grazing operations.

Obviously, buying beef isn’t as simple as I thought. These are some questions to ask yourself.

Is it grain fed?

Conventionally produced meat is fed grain, often in overcrowded feedlots, because it’s a cost-effective way to produce beef. Grain-fed cattle require less land than grass-fed animals, and they mature more quickly. The meat is well marbled with fat, which makes it tender, and many consumers like inexpensive, juicy meat.

I enjoy inexpensive, tender meat, too. But there are downsides to consider.

Learn more: Where's Your Beef Been?

The fatter animals become on grain, the more calories and saturated fat there are in the meat. Cattle also often get sick on a grain diet they weren't intended to eat in the first place and must be treated with antibiotics. Widespread use of low-dose antibiotics to promote speedy growth and prevent infection in livestock has contributed to antibiotic resistance in humans.

That began to change as of Jan. 1, 2017, when new Food and Drug Administration rules went into effect to limit routine use of antibiotics in cattle feed and water. Therapeutic use oral antibiotics important to human medicine for cattle feed now requires the veterinary equivalent of a prescription, and use of antibiotics to promote growth is banned.

Is it grass fed?

Grass-fed beef is popular among conscientious omnivores since it’s the animals’ natural diet. It’s healthier for humans too. Grass fed beef is lower in calories and saturated fat than grain-fed meat yet higher in healthy fats like conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and omega-3 fatty acids. Same goes for dairy products made with milk from grass-fed cows. (Although emerging research suggests saturated fat may not be the dietary no-no we've long believed.) Grass-fed beef also is higher in protein than conventional meat.

And because grass-fed beef is leaner, you’ll want to avoid overcooking it; rare to medium-rare is the way to go. Marinating helps tenderize it, too, as I did with this Grass-Fed Beef Bulgogi.

Until 2016, USDA’s voluntary Grass Fed Marketing Claim Standards specified that animals have a diet of forage (though that didn't guarantee they grazed in a pasture. “It opened the door to animals raised in a feedlot, fed harvested forage, given antibiotics and growth hormones, and labeled ‘grass fed,’” says Patricia Whisnant, DVM, owner of Rain Crow Ranch in Doniphan, Missouri, and president of the American Grassfed Association (AGA).

But the USDA rescinded even that tepid guideline, making it more difficult from consumers to know if their grass-fed beef is the real deal. Your best bet is to buy directly from a rancher and ask questions about the animals' feed and conditions (was it supplemented with grain? was it pasture raised?).

Or look for the AGA's American Grassfed certification logo to guarantee animals are raised on forage, in pastures, with no antibiotics and under humane conditions. The program includes third-party audits by Animal Welfare Approved. That's especially helpful when you're shopping at the store. Inexpensive grass-fed meat is often imported (Congress repealed mandatory Country of Origin Labeling for meat in 2016, so it's hard to know, really), which makes the standards murky at best — animals may be confined and fed a diet that only includes some grass.

Learn more: Considering Bison, the Other Red Meat

What about the cost?

Truly grass-fed, pasture-raised beef is expensive to produce. It requires plenty of land to accommodate cattle’s grazing needs, and animals take longer to mature. That means it costs more on the plate. Beef tenderloin is about $14 per pound for the conventional, grain-fed stuff while grass-fed, pastured beef is at least twice that.

But that's a price that more folks, especially those who follow Paleo and Whole 30 diets, which emphasize high-quality, minimally processed proteins, are willing to pay.

What role does organic play?

The USDA National Organic Program's access-to-pasture rule stipulates that all organic ruminant livestock must actively graze in a pasture during the grazing season in their location. It's a “pasture-based” system that requires grazing at least 120 days a year.

Sounds great, but that still leaves room for organic livestock to eat plenty of grain. “Grain can equal up to 70% of the diet,” Whisnant notes.

“A farmer could keep the stock in the feedlot for two days and then turn them out [to pasture] for one day, and continue that sequence year-round,” Gerrish explains. “The product of this would have essentially the same body composition profile of an animal continuously [fed grain] in the feedlot.”

How is it finished?

This is a livestock term that refers to how animals are fattened 90 to 160 days before slaughter, whether on grass or grain.

Grass finishing was standard until the 1950s, when grain finishing became the cost-effective norm. However, calories and overall fat in the animals’ tissues rise during grain finishing whereas grass-finished beef is lean.

What's the best cut?

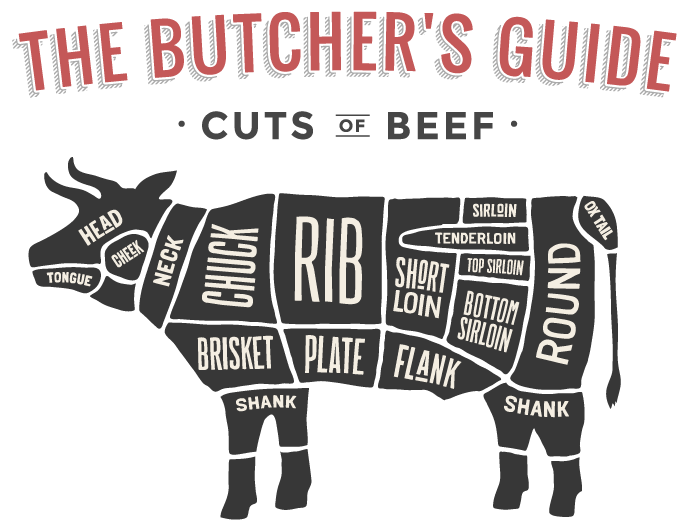

Whether you prefer grass-fed or grain-fed beef, you'll want to choose the best cut for your needs. It helps to know some basic cattle anatomy.

In general, cuts from hard-working muscles — chuck (shoulder) and round (haunch) — have lots of connective tissue. They also tend to be more affordable cuts. They do well braised, which cooks the meat in a moist environment at low heat to break down those tough fibers for meltingly tender results. Brisket is another tougher cut that benefits from low, slow cooking (think smoky, Texas-style barbecued brisket).

Learn more: The Basics of Braising

Rib cuts — as in a ribeye or rib roast — are tender, and more expensive than chuck or round cuts. Same goes for loin cuts, including top sirloin, Porterhouse, T-bone, tri tip and the most luxurious of all: filet mignon. These are the most tender cuts of all. No need to marinate these. They're delicious grilled, seared in a cast-iron skillet or popped under the broiler.

The plate yields short ribs (sublime braised) and skirt steak, a juicy, marbled cut that's delicious grilled. Flank steaks are a leaner alternative (and good candidates for marinating).

Here are a few of our favorite beef recipes to try:

- Spice-Rubbed Skirt Steak

- Beef and Barley Stew with Kohlrabi and Carrots

- Smoky-Sweet Tri Tip

- Beef Bulgogi

- Lia's Best Barbecue Ribs

- Homemade Corned Beef

- Braised and Glazed Five Spice Short Ribs

So what does all this mean on my plate?

We're fans of grass-fed beef for its health and animal-welfare advantages — and even for its premium price. Paying more encourages you to enjoy it (every bite) as an occasional treat in smaller portions on a plate where vegetables and whole grains take up most of the real estate.